Title: Re: Introduction - You can't see what I feel

Post by Rafael on Nov 27th, 2018 at 4:54pm

Quo Vadis?

You are what you are and you have what you have. But what good does that do in a normal life? Taking stock, the following is revealed:

I am sick and will remain so. My supply of medication is secured and my doctors even respond to e-mails in an emergency. I am known personally at my pharmacy and medical store. Nobody puts obstacles in my way. The logistics are there. My friends and family also know the score. Stories are shared at the self-help group, and my yoga class also promotes balance. Both also provide social contacts for free.

It almost sounds like a beautiful life. And it would be in an advertisement. The pharmaceutical companies like to use ads to suggest that after you take their medications, you'll feel even better than if you had never been sick at all.

But stepping back from the rosy world of marketing into the not-so-colourful reality, the first sentence always applies: I am sick and will remain so. And a regulated supply does not equal the elimination of symptoms.

There is no doubt that work and relationships are two central elements to any person's life. How does the disease, and working with it, specifically fit into one's professional life? (Observations as to how disease and relationships intermingle will follow in the next chapter.)

To be up front about it, work and cluster headache do not go together in many ways. It is quite exhausting to reconcile the two in some way. And it's hard for me to not get angry about this topic. It's even harder to find out what, or whom, I should even be angry at.

But I'd like to start from the beginning. My academic career was unremarkable and linear. After kindergarten and primary school I attended the Gymnasium, and graduated with a diploma after the normal period. I performed my community service thereafter. Then, with my university entrance qualifications in my pocket I attended the Ruhr University Bochum to study mechanical engineering. The extremely impersonal studies at this grey, concrete palace was not an environment entirely conducive to my own sense of happiness. I also had to involuntarily leave my parents' home around this time, and I was left to digest a not-so-pretty separation.

I counteracted this first bump in my life by changing colleges and attending the Bochum University of Applied Sciences. In retrospect I was not particularly worried about the future for the following period of time, to put it mildly. I worked odd jobs more than I studied. It got to the point that I was only attending classes once per semester, and that was just to enroll again. I was what is referred to as an eternal student. But because I was getting good work at the time, I wasn't much bothered by it.

I led my life away from a regulated nine-to-five office job. I wasn't really a dropout who sails around the world, but more like a soldier of fortune, though not an unhappy one. German TV-Truckers Franz Meersdonk and Günther Willers had had in impact on me. I got my truck driver's license and became the Jobbing King at a forwarding company. I was doing well, my job was fun, and I got the necessary respect in the form of cars fresh out of the factory. It was a nice time. It could have just gone on like that, and I would have stuck with the job. But when the company moved in the late 1990s, things would go differently from then on. I had to commute a very inconvenient distance.

At this time the EDP industry was booming and was now known as IT. Companies were all employing someone who knew how PCs tick. In the current of this IT boom I was easily able to switch from trucker to IT support. I actually knew enough about computers to be able to hold my own at my first job in the field. I also learned quickly on the job and was even able to improve my professional skills.

Admittedly, I was still an officially registered student. Yet I had not seen in the inside of a lecture hall in a long time, and I had taken just as few exams in all that time. I was now nearly 30 years old and was used to my life as a soldier of fortune. Nothing unusual happened to me. To look at it practically, I had at the very least arranged for my own survival, but not my future. I knew that, too, but I masterfully suppressed it. After all, I didn't have the worst job at a large computer retailer in Dortmund.

While this job went very smoothly, and I had a partner in my personal life whom I really wanted to be with, the disease slowly reached its hand out to me. I woke up ever more frequently in the night with infernal headaches. I tried one common headache medication after another, and in greater quantities, to no avail. Despite an entire series of tests, not one doctor was able to say what was wrong with me.

At least I knew that it wasn't a brain tumour, which I originally had a distinct and great fear of. Because these extremely severe pains always struck at the same location, I was certain that it must be something in my head that doesn't belong there. To this very day I still have the MR scans of my brain that thankfully don't show any such foreign bodies.

Three things then happened shortly thereafter. The pain not only came at night, but also during the day. The gold rush of the IT boom was over, and my company slowly began laying off all workers who didn't have children. This left me out on the street. Plagued by pain and unemployed, I no longer offered my partner any serious prospects and in this part of my life, too, I was soon out on a limb. (I will explain why I accepted this decision so easily in a later chapter.)

With that, my life collapsed into a shambles astonishingly quickly. Just turned 30, no professional prospects, and suffering from an unknown disease, I sat at home alone every night, knowing less and less what to do with my life. I thus found myself in the middle of a classic spiral of depression. My finances were approaching zero. My bank account was empty, my car was broken, and I had absolutely no idea how I would go on. It took a drastic turn of events in the form of a diagnosis of my disease just for me to get any kind of outlook on the future. After I finally knew what the enemy in my head was years later, I could deal with it first and then come up with ideas for a professional existence.

My CV was, of course, a disaster. With no completed higher education and with holes bigger than Swiss cheese, I had no need to form any realistic expectations of regular employment. Working independently was the fallback. So I tried holding my own by programming websites and repairing computers. It's no surprise that starting out is always difficult. In my case, however, continuing was just as hard. Anyone plagued by severe, constant pain for an average of three out of twelve months in the year cannot generate the finances to survive. I often had to cancel appointments, or hurried to the customer's toilet to take a shot of Imigran.

That was better than banging my throbbing head against the wall. In addition, the question wasn't how well that works, but for how long. Addled from the Imigran, I made more than one mistake and at least one time it would almost not have been able to be hidden or amended. I took this as a red flag, because the very real recourse claims following one serious mistake could not be my objective.

However, this episode was a step in the right direction. Thanks to contacts I had made and my disability which was now recognised, it was possible for me to have an education individually funded by the labour committee. Two years after signing the agreement, I passed my final exams and have since been a digital and print media designer: design and technology.

I had tinkered with computers for years, and in that time I learned that educated technicians are not necessarily more competent than I am. So I spoke before the Chamber of Industry and Commerce and was given the chance to take an external exam. Four months later I passed this test as well. Now I can not only call myself a media designer, but also a system integration technician.

It sounds good, and it also felt very good. Now everything could be good, or at the very least better. But, sadly, it wasn't. After my last exams I felt like I had fallen into a hole. Yet the headache journal quite prosaically revealed that the number of headache attacks had continued to rise one month before. If the exams had been just one or two weeks later, the result probably would have looked different. And although time and feeling would have been kicking off again, my head was very stubbornly thwarting my plans, because what followed was one of the most intense episodes up until that time.

Following my small round of exams was an episode at the epicentre of which I could not sleep for one entire night over 18 straight weeks, and experienced up to six attacks per day. At the end I had a new medication schedule and multiple treatments that helped me get back on my feet. I ultimately landed in competent facilities and was able to learn a lot about coping strategies and acceptance of the disease.

Regardless, it would take well over a year for me to turn my inward perspective back outward. That is where I stand now. Despite my handicap brought on by chronic illness, I now have two professions and am no longer without any higher education.

But my life story is by no means a textbook example. It will surely continue to be a source of furrowed brows and shaking heads among the decision-makers at HR departments. This doesn't bode well for my competitive chances. Not to mention that I misjudged myself with my choice of career. The employers of media designers and IT specialists are quite frequently small agencies who are, in practice, at the mercy of the needs, desires, and moods of the customer. In the advertisement the customer provides the required materials at the last minute at the earliest, but still sets the deadline for "yesterday". Of course this results in irregular work hours and peak periods of stress that I am no longer built for.

The modern world is a society of output that I can't keep up with anymore. Because I was a soldier of fortune in my first decade on the workforce, I unfortunately never put down roots that allow me to remain employed despite my disability. So I try finding a new field to work in. However, what that field exactly is has remained unclear both to myself and to anyone else. My disability cannot be fathomed, not by me and especially not by a third party. After all, pain cannot be seen and I have no way of predicting when the next episode that is so intense that I am completely unemployable once more will occur.

I only know that even in symptom-free times, I can no longer compete with healthy candidates. Even though cluster headache isn't a psychosomatic disease, every form of stress and overstimulation has palpable negative consequences. I have to consider whether that suits me or not in the interest of self-responsibility. I should even try not getting angry at the fact that I can no longer do things the way I would like to. That, too, is a form of stress and it leads to spirals with a current pulling in the wrong direction.

Presently, I'm fascinated by people who don't have a career in order to accumulate as much material profit as possible, but rather who pursue a career that fulfils them. Naturally I would be happy to not depend on material things, but career and wealth don't constitute worthy objectives for me anymore. I can't imagine being any happier with 5,000 euros per month than I would be with 1,500 euros. But someone with 1,500 euros is happier than they would be with 500. With income that low, the person is too close to the poverty line, and by definition they are even below it. Great restrictions have to be set, and a broken washing machine becomes an immense problem, and the result is more stress.

Isn't it wonderful that a severe, chronic disease that causes permanent disability makes one into a more frugal person?

Now to get back to the harsh world of work. Nearly every job ad seeks applicants who are as flexible and durable as possible. I have even found the word "stress-resistant" as a requirement before. The society of output cannot be proclaimed any clearer than that. When I read such ads all I can do is let out a quiet sigh. I cannot meet these requirements without hurting myself in the process. But then I keep on reading until I find the attributes I seek: "diligent" or "thorough".

So why not just go back to school for a new trade? Because I'm not a bricklayer with bad knees, or a construction worker with a bad back. I'm severely disabled. I have actually been invited to such interviews after my benefits expired upon 78 weeks of unemployment. And the problem wasn't that nobody wanted to help out. Rather, it's finding something suitable. To exaggerate slightly, I suffer from a social intolerance.

This situation always results in creative to ludicrous ideas: professions often beyond the realm of most normal people, like glass eye designer, stonecutter, or shepherd suddenly seem quite interesting. But there are far too few open positions in these fields, and so the ideas remain ideas.

For a long time there was no clear solution to this dilemma in sight. The only thing that was certain was that trying nothing is also a conscious decision - and the worst. You can never be one hundred per cent sure that something is going to work. But you can be absolutely certain that doing nothing will never work. Either way, a solution can suddenly appear out of thin air. Things can happen that can neither be planned nor predicted.

This is the fortune that befell me when I ultimately found a suitable job. When all is said and done, my only confession is that I am not built for a full-time, 40-hour workweek, and perhaps I never will be. But this applies to all jobs, and I can't hold that against them. Once it was out of style, I was able to learn that there are still professions in which a human being is treated like one instead of walking capital.

|

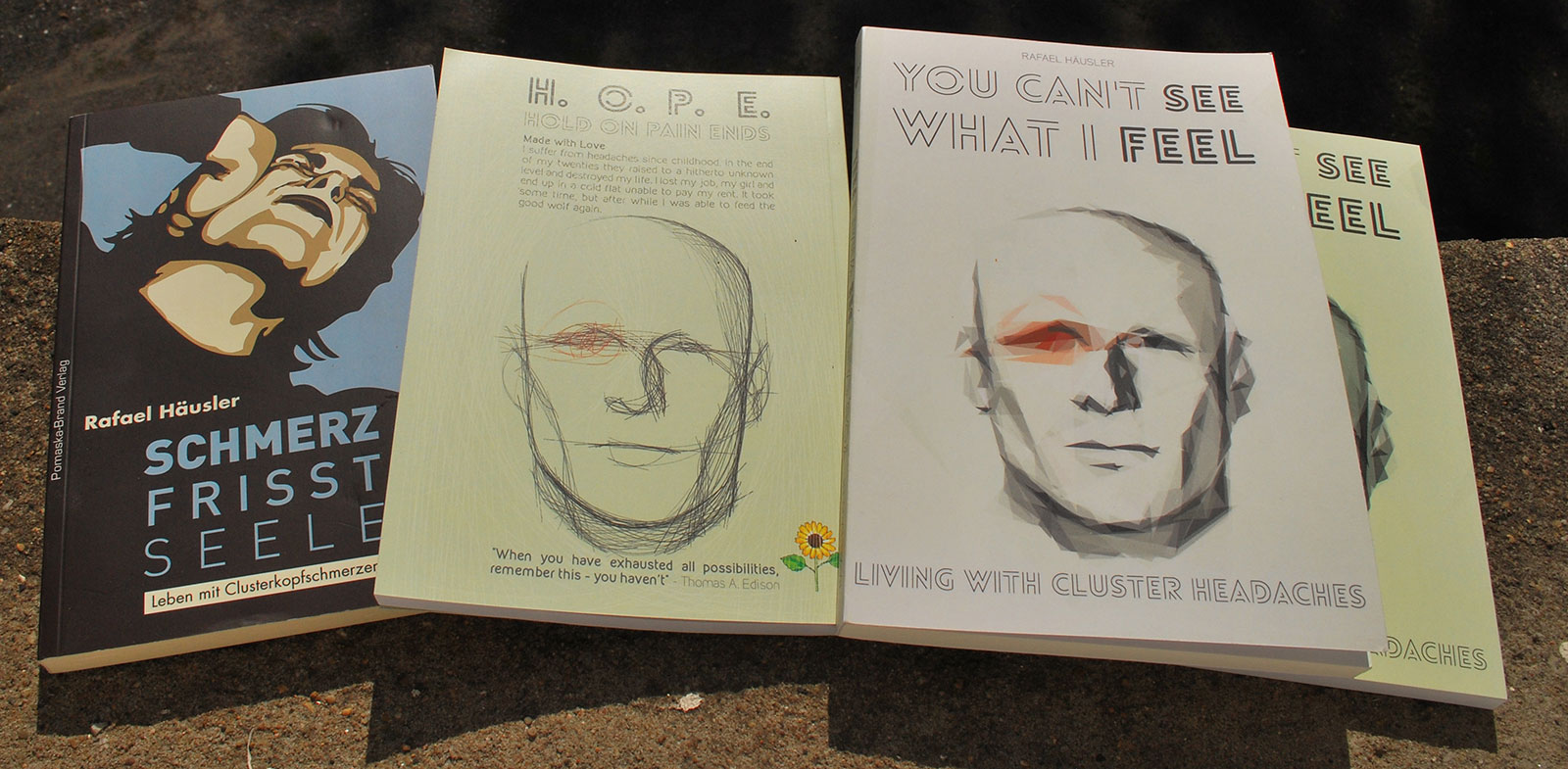

YcswIf.jpg (255 KB | 1

)

YcswIf.jpg (255 KB | 1

) YcswIf.jpg (255 KB | 1

)

YcswIf.jpg (255 KB | 1

)